Early Ancestors of the Golden Retriever

By Mrs. Mark D. Elliott

Several years ago my attention was called to an article by Mrs. Elma Stonex in the British “Dog World” Magazine revealing facts of origin about the Golden Retriever which refuted the colorful and romantic story of the Russian circus dogs as the forebears of the breed. That anyone should doubt this story was like a shocking intrusion into the well ordered pattern of one’s personal history. In striking contrast to the background so long attributed to Goldens, the article acknowledged their descent from black Wavy Coated Retrievers and Tweed Water Spaniels–the latter breed long lost in obscurity and about which little information had been found.

My curiosity aroused, I entered the search, and by chance came across a description in an old and rare copy of Dalziel’s British Dogs in—of all surprising places—the chapter on Irish Water Spaniels. More reluctant than ever to concede any connection between the Tweed dogs and our lovely Goldens, I sent this reference to the author of the articles. A most interesting and informative correspondence followed, and through her patience and kindness I soon became a convert to the new findings. Mrs. Stonex is considered one of the foremost authorities on Golden Retrievers today, and she has shared with us facts, photographs and pedigrees which relate the true beginnings of the breed.

Her research had been stimulated by information published in the British “Country Life” Magazine early in 1952 and 1953 which had been contributed by the Earl of Ilchester who had recognized the need for making public what he knew about the yellow retrievers before it became too late. Lord Ilchester not only recounted his own experiences before the turn of the century but disclosed recently discovered notes written by his great uncle, Sir Dudley Marjoribanks (pronounced Marshbanks), who was later known as LordTweedmouth. Sir Dudley founded the Golden Retriever breed and his kennel records establish for certain the logical relationship between Goldens and other retriever varieties.

Until the discovery of the Tweedmouth stud book, few people had challenged the legend surrounding the background of “Nous”, the foundation sire, as he was believed by most to have been one of a troupe of trick dogs imported from Russia known as Russian Trackers. Mrs. W. A. Charlesworth, owner of the celebrated Noranby Kennels from nearly five decades earlier, and author of the popular and widely distributed Book of the Golden Retriever (1932), had championed the story of the Russian origin with such fervor that the voices of skeptics had been quite suppressed. Just before Lord Ilchester’s articles appeared, however, a book entitled Dogs Since 1900 was published. Its author, Mr. A. Croxton-Smith, here tells how over a long period of time he had given wide publicity to the story of the circus dogs, but, after talking directly with descendants of the original breeder, he had become convinced that the Russian origin was but a myth. This is what he says:

“Col. Ie Poer Trench ( St. Hubert’s Kennel) told me a romantic story which I was responsible for reporting extensively in various articles, to the effect that Sir Dudley Marjoribanks founded his kennel on a troupe of performing dogs that he bought from a circus proprietor in Brighton soon after the Crimean War. My old friend told me this story with such conviction that I had no reason to doubt it, but when I saw descendants of Mr. Harcourt’s strain (Culham} I came to the conclusion that they were not greatly different from the FlatCoats that I used to know when a boy, and I thought the best way of getting an accurate version of the origin of the Guisachan dogs was to go to the late Lord Tweedmouth who was the grandson of the first peer.

“He told me that one Sunday when his grandfather and father were at Brighton in the late ’60’s, they met a good looking yellow retriever and approached the man who had it. This man, who was a cobbler, said that he had received the dog in lieu of a bad debt from a keeper in the neighbourhood and that it was the only yellow puppy out of a black Wavy-Coated (the Flat Coats were then called Wavy) Retriever litter. Sir Dudley bought the dog and later obtained a bitch of a similar colour in the Border country. Several others were obtained, and to prevent the danger of excessive inbreeding, an occasional outcross was made with black Flat-Coated bitches. The third Lord Tweedmouth assured me that there was never a trace of Bloodhound in them — they were absolutely purebred Retriever.

“This version had corroboration in a letter published in the ‘Field’ in 1941, when M. S. H. Whitbread stated that the second Lord Tweedmouth told him how, as a small boy at school near Brighton, his father, Sir Dudley Marjoribanks, took him for a walk on the downs where they met a man with a very handsome young yellow retriever. He was a shoemaker and had received the puppy from Obed Miles, the keeper at Stanmer, in payment for a bill. Sir Dudley bought the dog, which was the originator of the Tweedmouth breed.

“Reading these two accounts together, combined with my previous doubts, I feel we must accept them as being correct.”

One cannot disregard the fact that dogs of Russian origin did come into England during the 19th century and especially after the time of the Crimean War. The Russian Pointer, the Russian

Setter and the Russian Retriever are described in detail in numerous writings, but the descriptions of appearance as well as temperament are incongruous with those of the dogs, which Lord Tweedmouth recorded as being in his kennel. If he did use any Russian dogs in experimental crosses the notations do not show it. The first British show registry, which covers the years 1859-73, listed a retriever named “Sultan” bred by Lord Tweedmouth’s son E. Marjoribanks, which was by ” Moscow” out of a Tweed Water Spaniel. But names with Russian connotation were found in other breeds, as well, and since this breeding was not mentioned elsewhere it would seem probable that the nomenclature was influenced by the war. Knowing of this registration, however, may lend some comfort to those whose love of mystery makes it difficult to give up completely all connection with the legend of the circus dogs.

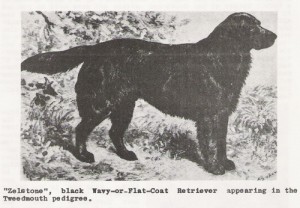

The Wavy-Coated Retrievers were ascending the height of popularity in the mid-1800’s when Sir Dudley took an interest in developing the yellow variety. The Curly-Coats had already come into their own. Flat-Coats, as the name would imply, were a later modification of the Wavies, and both were classified in the British Kennel Club registry as Wavy-or-Flat-Coated Retrievers. Labradors were also becoming popular but these, like the yellows, were listed among the Wavy-or-Flat-Coats until after 1900, and were identified mainly where color and coat or breeder were mentioned.

One of many keen sportsmen, Sir Dudley had watched with interest the emergence of different retriever types. His kennel records, which date from 1835, show that at one time or another he owned and bred beagles, pointers, setters, greyhounds, Scottish Deerhounds and Irish Water Spaniels. In 1854 he moved to his Guisachan estate (pronounced goowissican) near Beauly, Scotland, and about a decade later obtained the foundation stock for the breeding program which was to make such an impact on the world of dogs.

As a mate for the reportedly handsome “Nous” (meaning wisdom), the light colored pup from a litter of black Wavy-Coats, he selected “Belle”, a Tweed Water Spaniel which had been given him by a relative who lived at Ladykirk, located on the River Tweed along the Border country. “Belle” was the second Tweed Spaniel to appear in his kennel notes, the first having died at an early age. From what we can learn about these dogs–if one is to question Lord Tweedmouth’s choice–it would appear that the selection could not have been made to enhance beauty, but rather to intensify the aquatic ability and the already pleasant character of the Wavy-Coats. For in giving thought to Sir Dudley’s program, and considering the variety apparent in the early yellow retrievers, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that character, temperament and usability outranked his concern for uniformity.

The black Wavy-Coats had acquired beauty and nobility, courage, love of water and keen scenting ability from their Newfoundland and setter forebears from which combination they are known to have descended. It is important, however, to identify the type of Newfoundland referred to in the line of descent, as there was more than one variety. To develop retrievers of the desired moderate size it would not have been practical to resort to the massive Newfoundland such as we know today or such as had been known in England long before. Credit must be given to the St. John’s Newfoundland which first appeared on the shores of England in the early 1800’s aboard fishing vessels from North America. Because of the proximity of the provinces whence they came, the St. John’s Dogs were also referred to as Labradors. Their influence on all retriever breeds is indisputable, but the early nomenclature must not be confused with the pure breed of Labrador developed several decades later. The smaller Newfoundland is believed to have been indigenous to the provinces, while the larger variety with their tremendous coats resulted from crosses with Pyrenean Mountain Dogs which came with ships from Spain.

An illuminating description of the St. John’s type was included in an article entitled “The Retrievers” in an 1839 issue of the British “Sportsman”. “It may not be amiss here,” the writer said, “to observe that the large dog so frequently seen in this country (England), passing under the denomination of Newfoundland, is not the genuine dog of that country; the real Newfoundland dog is about as large as a setter, but in general conformation more resembling the beagle; strong, active and remarkably sagacious; he is well calculated for retrieving.” The mental picture derived from these comments is described with a remarkable degree of similarity in the breed standard for the “St. John’s Dog or Labrador” as outlined by Stonehenge several years later.

A prolific writer whose travels took him to many parts of the world was General W. N. Hutchinson who recorded countless observations and anecdotes from his own experiences. About retrievers he wrote, “From education there are good retrievers of many breeds, but it is usually allowed that, as a general rule, the best land retrievers are bred from a cross between the setter and the Newfoundland—or the strong spaniel and the Newfoundland. I do not mean the heavy Labrador, whose width and bulk is valued because it adds to his power of draught, nor the Newfoundland increased in size at Halifax and St. John’s to suit the taste of the English purchaser, — but the far slighter dog reared by the settlers on the coast, — a dog that is quite as fond of water as of land, and which in almost the severest part of a North American winter will remain on the edge of a rock for hours together, watching intently for anything the passing waves may carry near him. Such a dog is highly prized. Without his aid the farmer would secure but few of the many wild ducks he shoots at certain seasons of the year. The patience with which he waits for a shot on the top of a high cliff — until the numerous flocks sail leisurely underneath — would be fruitless did not his noble dog fearlessly plunge in from the greatest height, and successfully bring the slain to shore.”

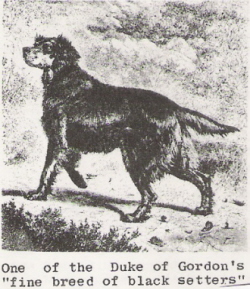

Hutchinson also specified which of the setters he felt made the best cross. “Probably a cross from the heavy, large-headed setter, who, though so wanting in pace, has an exquisite nose, and the true Newfoundland makes the best retriever. Nose is the first consideration.” There is no doubt that all setter varieties were tried, but this comment suggests the type for which the Duke of Gordon became famous, as the “Gordons” had the reputation of being easier to train than the others, though were not so fast in the field. Said the illustrious author Idstone, “I have seen better Setters of the black and tan variety than of any other breed.” The Duke also had a strain of fine black Setters – and in deliberating over the accompanying sketch, one can be tempted to side with the proponents of the Gordon cross. However debatable such conjecture may be, it is interesting to know that mingled in the Gordon blood was that of the Irish Setters and Bloodhounds.

The cross between the St. John’s Newfoundland and the Setter produced greater versatility, more supple body structure, and freer action. The neck showed greater length permitting more ease “in stooping for scent”, the chest became somewhat narrower and deeper allowing for more oblique shoulders, and there was an improvement in bend of stifle.

In litters of black retrievers there occasionally appeared puppies of yellow color. Biologically speaking, such deviations from the normal pattern are classified as sports or mutations. So in the light of the information given us by Lord Ilchester and corroborated by the authoritative writer, A. Croxton-Smith, together with Lord Tweedmouth’s kennel notations, it can be safely assumed that such a puppy was “Nous”, the light colored whelp from the litter of black Wavy-Coats that had been bred by Lord Chichester in Brighton in the year 1863. And four years later this dog was mated to “Belle”, a “bitch of similar colour from along the Border country,” which we now know was a Tweed Water Spaniel.

If Lord Tweedmouth appreciated the beauty of the Wavy-Coats, it seems unlikely that the looks of the early Water Spaniels could have commanded his admiration. Quoting his friend, J.S. Skidmore, Mr. Dalziel describes the Tweed dogs as follows:

“When I first commenced to keep Irish Water Spaniels, many years ago, there were three strains, or rather varieties–one known as the Tweed Spaniel, having its origin in the neighborhood of the river of that name. They were very light liver colour, so close in curl as to give me the idea that they had originally been a cross from a smooth-haired dog; they were long in tail, ears heavy in flesh and hard like a hound’s, but only slightly feathered; forelegs feathered behind, hind legs smooth; head conical; lips more pendulous than M’Carthy’s strain. The one I owned, which was considered one of the best, I bred from twice, and in each litter several of the puppies were liver and tan, being tanned from the knees downward, and under the tail. I came to the conclusion that she, at any rate, had been crossed with the Bloodhound.”

Stonehenge, in his well known publication The Dog, who dissertates at length on the spaniels of Ireland, dismisses the Water Spaniels in England as being of “indefinite character”-yet devotes several paragraphs in high praise of their versatility and temperament. About the Tweed Water Spaniel’s appearance, he said, ”The Tweed Water Spaniel resembled a good deal a small ordinary English Retriever of a liver colour.”

Stonehenge, in his well known publication The Dog, who dissertates at length on the spaniels of Ireland, dismisses the Water Spaniels in England as being of “indefinite character”-yet devotes several paragraphs in high praise of their versatility and temperament. About the Tweed Water Spaniel’s appearance, he said, ”The Tweed Water Spaniel resembled a good deal a small ordinary English Retriever of a liver colour.”

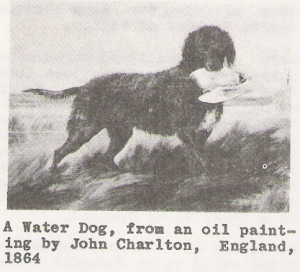

In recognition of the fact that Water Spaniels were variously referred to as Water Retrievers, Water Dogs, and even Water Dog Retrievers, it seems likely that the English Retriever could have had some connection with the old English Water Spaniel, a breed which has also been lost in obscurity. If this was so, Stonehenge has given us a clue, because descriptions of the latter spaniels are more readily found.

The English and Tweed Water Spaniels showed a particular similarity in shape of head, both being conical (slightly pointed) without being snipey, with smooth forefaces, no foretop and ears of medium length. The English variety carried a longer coat, however, though it was closely curled without being shaggy and the tail was often—not always—docked. The color of the latter varied a good deal–black, black and white, liver and liver and white.

Interesting importance was attached to color in those early days. Black was believed “to be the best and hardiest and least susceptible to fatigue, hunger and danger; the spotted, or pied, quickest of scent and sagacity; and the liver-coloured the most alert and expeditious in swimming.” (Liver meant almost any shade from brown to yellow.)

Interesting importance was attached to color in those early days. Black was believed “to be the best and hardiest and least susceptible to fatigue, hunger and danger; the spotted, or pied, quickest of scent and sagacity; and the liver-coloured the most alert and expeditious in swimming.” (Liver meant almost any shade from brown to yellow.)

Mr. Stanley O’Neill, famous for his knowledge of Flat-Coated Retrievers, recalls having seen a Tweed Water Spaniel when he was a boy close to the turn of the century. He wrote Mrs. Stonex that he often visited the fishing ports with his father who was Superintendent of Grimsby Fish Docks. ”Further up the coast,” he said, “probably Alnmouth, I saw men netting for salmon. With them was a dog with a wavy or curly coat. It was a tawny colour but, wet and spumy, it was difficult to see the exact colour, or how much was due to bleach and salt. Whilst my elders discussed the fishing I asked these Northumberland salmon net men whether their dog was a Water-Dog (there were many Water Dogs along the coast of Great Britain) or a Curly, airing my knowledge. They told me he was a Tweed Water Spaniel. This was a new one on me. I had a nasty suspicion my leg was being pulled. This dog looked like a brown Water Dog to me, certainly retrieverish, and not at all spanielly. I asked if he came from a trawler, and was told it came from Berwick.”

Mrs. Stonex also quoted Mr. O’Neill as telling her a close friend of his from a long-established Berwick family as recently as 1921 informed him that the Tweed Water Spaniel was the same as the Water Dogs to be seen all up the east coast from Yarmouth to Shields. The only difference between the Shields dogs and those further south was that the percentage of browns and yellows was much higher on the Border; some people said they predominated.

But “our sporting forefathers were practical men and showed they were so in their selection of dogs suited to the work to be done.” If not always beauty in the Water Spaniels, they consistently found qualities of unsurpassed intelligence and steadiness of temperament, combined with water prowess and willingness to work. To this fact all writers give testimony.

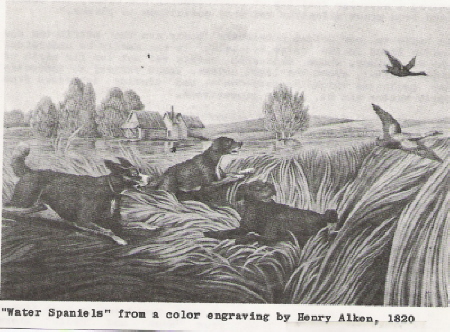

Descended from crosses between the land spaniels and the early Water Dogs “Somewhat big, and of measurable greatness, having long, rough and curled hair.” The Water Spaniels were an integral part of the families who lived along the rugged shoreline and who depended on their courage and retrieving ability to keep meat on the table. In comparing the virtues of the Water Spaniel and the Land Spaniel, William Youatt wrote, ”The Water Spaniel although when at his work being all that his master can desire, is when unemployed, comparatively a slow and inactive dog; but under this sobriety of demeanor is concealed a strength and fidelity of attachment to which the more lively Land Spaniel cannot always lay just claim….He is artful, careful, and above all not too noisy; slipped from the punt or shed it is long odds against the wounded mallard, so good are they in nose and so unceasing in their endeavors to please.”

As in the ballads of old, other early writers chant the virtues of the Water Spaniel. “He rushes in with the most incredible fortitude and impetuosity, through and over every obstacle that can present itself, to the execution of his office. For whether the fowl fall dead amidst the infinite clefts, recesses, and vacuities of rock, or, being only winged or wounded, and falling into the water, it is the distinguished property of this dog never to recede till he has performed his task, and brought the object of his mission to the hand of his master.”1 “He is particularly fond of water and will enter it in almost all weathers by choice, while it never is too cold for him when any game is on it. His powers of swimming and diving are immense, and he will continue in it for hours together, after which he gives his coat a shake and is soon dry…He rivals every other breed in his attachment to his master.”

In a significant tribute to the Tweed Water Spaniel, Hutchinson relates the story of how a blind man depended on one for guidance: “When recently salmon-fishing on the upper parts of the Tweed, I occasionally met on its banks a totally blind man and who, in spite of this great disqualification, continued a keen and successful trout angler. He had been for some years entirely sightless, and was led about by a large brown Tweed-side spaniel, of whose intelligence wonderful stories were told. M—r traveled much around the country; and it is certain, for he would frequently do so to show off the dog’s obedience, that on his saying (the cord being perfectly slack) ‘Hie off to the Holms or Hie off to Melrose,’ etc., the animal would start off in the right direction without an instant’s hesitation. Now this Tweed Spaniel was not born with more brains than other Tweed Spaniels, but he was MI–r’s constant companion, and had, in consequence, acquired a singular facility of comprehending his order, and doubtless from great affection was very solicitous to please.”

So basic to our Golden Retrievers today are the attributes and traits found in the Water Spaniels, it can easily be understood why Sir Dudley, whose Guisachan estate was not too far north of their habitat, choose the light colored Tweed variety to intensify the qualities which the Wavy-Coats had already inherited from their setter and St. John’s progenitors.

In developing his strain of yellow retrievers, he might have enjoyed a friendly rivalry with fellow sportsmen bent on perfecting other retriever types for as wildfowling became the sport supreme during the latter half of the 19th century the demand for retrievers grew. Breeders then, as now, had their preferences; and while their methods for developing type differed, they recognized the need for gundogs of moderate size with strength and intelligence, and the courage to withstand all kinds of weather and arduous hunting conditions. Suffice it to say the advent of dog shows stimulated the standardizing of definite types and consistency of color. “I know of no breed of dog that supplies a better companion for town or country,” said writer and judge Hugh Dalziel, “than the Wavy-Coated Retriever, being of middle size, not too big for the house, but big enough to carry some dignity of appearance, and also to be a useful protector, should such service be required of him.”

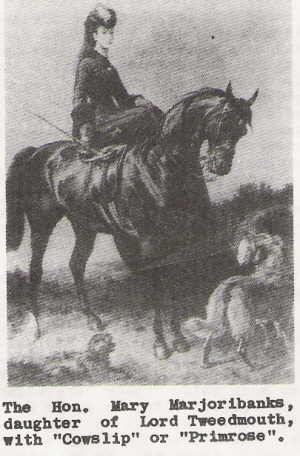

In Lord Tweedmouth’s 1868 litter from “Nous” and “Belle” there were four yellow puppies–“Crocus”, “Primrose”, “Cowslip”, and “Ada”. How vivid and light a color this nomenclature suggests: The accompanying illustration shows “Cowslip” or “Primrose” with Lord Tweedmouth’s daughter. “Crocus” and ” Ada” are pictured in Mrs. Stonex’s Golden Retriever Handbook.

In Lord Tweedmouth’s 1868 litter from “Nous” and “Belle” there were four yellow puppies–“Crocus”, “Primrose”, “Cowslip”, and “Ada”. How vivid and light a color this nomenclature suggests: The accompanying illustration shows “Cowslip” or “Primrose” with Lord Tweedmouth’s daughter. “Crocus” and ” Ada” are pictured in Mrs. Stonex’s Golden Retriever Handbook.

For readers who may question why black puppies do not appear in Golden Retriever litters, without entering the details of genetics, here is a brief quotation from a brochure entitled “The Inheritance of Dominant and Recessive Characteristics”, written by Miss Edna Dubuis of the Roscoe Memorial Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. First mentioning the dominance of black genes, the author says, “Dominant characteristics appear in successive generations, and even though an animal is descended from a long line of ancestors, all of whom showed a certain dominant trait, that animal cannot hand down the trait to his or her offspring unless the trait appears in that individual. Thus a red Cocker, descended from four or five generations of black Cockers, cannot hand down the color black. The dominant color (black) has been lost in the red individual; it is not seen because it is not there. A recessive cannot conceal a dominant gene.”

Through the great kindness of Mrs. Stonex, we are able to include here an early pedigree which she worked out from Lord Tweedmouth’s stud book, adding notations from her own research into British Kennel Club registrations. The pedigree shows the use of “Cowslip” in a program of careful linebreeding to set type and character. A second Tweed Spaniel was introduced to keep the line strong and occasionally outcrosses were made to black Wavy-or-Flat Coats. An Irish Setter was brought in, undoubtedly to enrich the coat color and assure continuance of keen power of scent. And the records show the later use of a sandy colored Bloodhound which Lord Ilchester said was to improve tracking ability. Coat color varied greatly—Croxton-Smith commented that the term “yellow” included all shades from fox red to cream.

Several of the Flat Coats in this pedigree – “ Paris”, “Thorn”, “Dusk” and “Trace” – are described in Vero Shaw’s Book of the Dog (1881) as some of the best in the kennel of Mr. E. S. Shirley, most prominent of the early Flat-Coat breeders. The sire and dam of “ Paris” were imported directly from Labrador. Mr. Shirley told Dalziel that the “Thorn” stock crossed with that of “ Paris” blood was better for work. So here is further proof that Tweedmouth knew what he was aiming for and drew only from the best. Mr. O’Neill, whom was mentioned before, made a telling statement about a famous Flat-Coat named “Darenth” as being the “tap-root of all modern Flat-Coats and ancestor of Goldens through his immediate descendants used in the Ingestre Kennels.”1 “Darenth” was a paternal grandson of the bitch “Think” which appears in the Tweedmouth pedigree given here.

Several of the Flat Coats in this pedigree – “ Paris”, “Thorn”, “Dusk” and “Trace” – are described in Vero Shaw’s Book of the Dog (1881) as some of the best in the kennel of Mr. E. S. Shirley, most prominent of the early Flat-Coat breeders. The sire and dam of “ Paris” were imported directly from Labrador. Mr. Shirley told Dalziel that the “Thorn” stock crossed with that of “ Paris” blood was better for work. So here is further proof that Tweedmouth knew what he was aiming for and drew only from the best. Mr. O’Neill, whom was mentioned before, made a telling statement about a famous Flat-Coat named “Darenth” as being the “tap-root of all modern Flat-Coats and ancestor of Goldens through his immediate descendants used in the Ingestre Kennels.”1 “Darenth” was a paternal grandson of the bitch “Think” which appears in the Tweedmouth pedigree given here.

It is unfortunate that the Tweedmouth and Ilchester families did not register their dogs – they apparently never guessed what a popular destiny awaited the yellows! Numerous names appear in the British registry with sires or dams of their breeding, however, which definitely link the later yellow retrievers with the Guisachan strain. A few dogs were given to the Earl of Shewsbury whose Ingestre Kennel, well known for its Flat-Coats both black and yellow, appears in the background of nearly all Goldens today. Kennel programs differed, as we have said, but all helped to widen public interest in the light colored Retrievers. Of no small influence in their rise to acclaim was their outstanding work in field trials around the turn of the present century, among them being “Don of Gerwyn”, a liver coated son of a Tweedmouth dog named “Lucifer”, who won the International Gundog League trial in 1904.

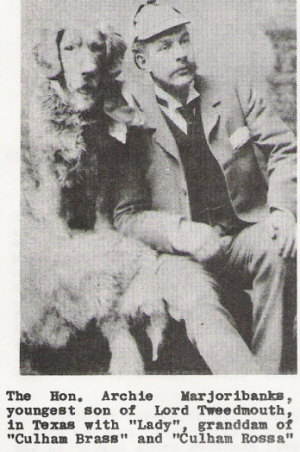

Opening the gateway for generations to follow were “Culham Brass” and “Culham Rossa”, first to be registered under the famous Culham prefix and among the earliest to be shown as Yellow or Golden Retrievers. These two dogs had been raised by Mr. John McLennan, a former keeper at the Guisachan estate and were sold as puppies to Lord Harcourt who owned the Culham Kennel. Lord Harcourt had also received other Guisachan Retrievers from Edward Marjoribanks, Lord Tweedmouth II, after his father’s death, and these he also showed. From “Brass” and “Rossa” came “Culham Copper”, sire of “Ch. Noranby Campfire”—the first Golden ever to win a bench title. “Copper” also sired “Culham Tip” (out of “Beena” of Ingestre parentage, said to have been dark red in color). “Campfire’s” dam was the great foundation bitch of the Noranby Kennel, “Normanby Beauty”, whose pedigree is not known. “Beauty”, in a later mating with “Culham Brass”, produced “Noranby Balfour”, who shared the prestige of “Campfire” and “Tip” as progenitors of unchallenged influence.

Quite inadvertently, Mrs. Stonex has helped to establish the year when Goldens were first introduced to the American continent. She sent me a photograph of the Hon. Archie Marjoribanks, son of the first peer, taken at the Rocking Chair Ranch in Texas where he was living between 1891 and 1894. With him is the Yellow Retriever “Lady”, grandam of Lord Harcourt’s “Brass” and “Rossa”. Hon. Marjoribanks also brought with him a nine year old retriever named ”Sol” who was out of “Zoe”, granddaughter of ” Tweed” and “Cowslip”. “Sol” died at the ranch, but “Lady” accompanied him to Cold Stream, Mt. Vernon, British Columbia, where Marjoribanks visited his sister, the Marchioness of Aberdeen and her husband, Lord Aberdeen, who was Governor General of Canada. Quite possibly the Aberdeens, too, had retrievers with them, as references to Goldens in that area have always been in the plural. However, until this information came to light, no one seemed to know for certain about their identity, except to say that they had been brought from England by retired army officers around 1900. Another son of the first Lord Tweedmouth, Couts Marjoribanks, lived for a time in North Dakota where he raised Aberdeen cattle.

Quite inadvertently, Mrs. Stonex has helped to establish the year when Goldens were first introduced to the American continent. She sent me a photograph of the Hon. Archie Marjoribanks, son of the first peer, taken at the Rocking Chair Ranch in Texas where he was living between 1891 and 1894. With him is the Yellow Retriever “Lady”, grandam of Lord Harcourt’s “Brass” and “Rossa”. Hon. Marjoribanks also brought with him a nine year old retriever named ”Sol” who was out of “Zoe”, granddaughter of ” Tweed” and “Cowslip”. “Sol” died at the ranch, but “Lady” accompanied him to Cold Stream, Mt. Vernon, British Columbia, where Marjoribanks visited his sister, the Marchioness of Aberdeen and her husband, Lord Aberdeen, who was Governor General of Canada. Quite possibly the Aberdeens, too, had retrievers with them, as references to Goldens in that area have always been in the plural. However, until this information came to light, no one seemed to know for certain about their identity, except to say that they had been brought from England by retired army officers around 1900. Another son of the first Lord Tweedmouth, Couts Marjoribanks, lived for a time in North Dakota where he raised Aberdeen cattle.

The descendants of the Marjoribanks retrievers spread up and down the coast, some of them reaching Alaska, but unfortunately neither the British nor Canadian Kennel Clubs had recognized the breed at the time and specific identity is lost. When Colonel Magoffin purchased the famous Gilnockie Kennel in Vancouver, three decades later, he imported all of his breeding stock and claims no connection with the dogs which were there before. But how close the relationship.

Shortly after the founding of the Golden Retriever Club of England, in 1911, the British Kennel Club granted official recognition to the yellow retrievers as a separate variety, classifying them as “Yellow or Golden”. A few years later the name “Yellow” was dropped altogether. Goldens were recognized in the United States in 1932 and the Golden Retriever Club of America was organized in 1939—which, like its English predecessor, is dedicated to the welfare of Golden Retrievers whose popularity can hold merit only as long as breeders are conscientious in their efforts to safeguard the inherent qualities of temperament, working ability and type such as Lord Tweedmouth and his followers strove to attain.

Rachel W. Elliott

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Croxton-Smith, A., Dogs Since 1900, London, 1950

Dalziel, Hugh, British Dogs, c. 1881, London

Hubbard, Clifford, L. B., Literature of British Dogs, London, 1948,

Hutchinson , W. N., Dog Breaking, London, 1848

Shaw, Vero, Book of the Dog, London, 1881

Stonehenge (J. C. Walsh), The Dog, London, 1884, 4th Edition

Vezey-Fitzgerald, Brian, The Book of the Dog, Los Angeles and Toronto, 1948

Youatt, William, The Dog, London, 1854

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Appreciation is expressed to Lady Pentland, granddaughter of Lord Tweedmouth, through whose courtesy Lord Tweedmouth’s Kennel Records and family photographs were made available to Mrs. Stonex. Appreciation is also expressed to Mrs. Carlton Howe for information which helped in the writing of this article.

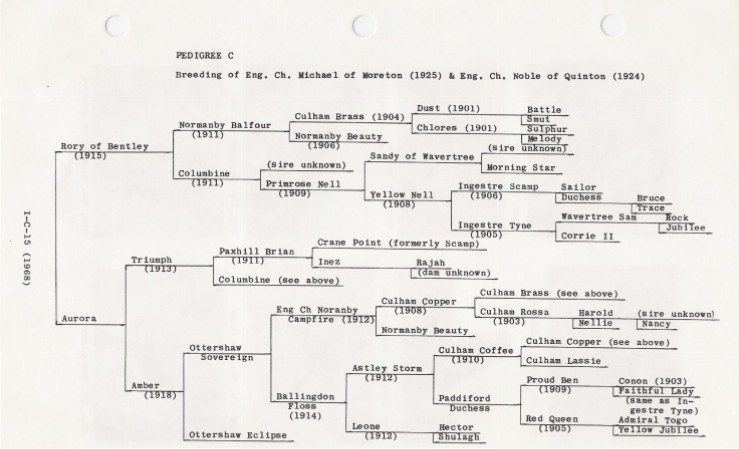

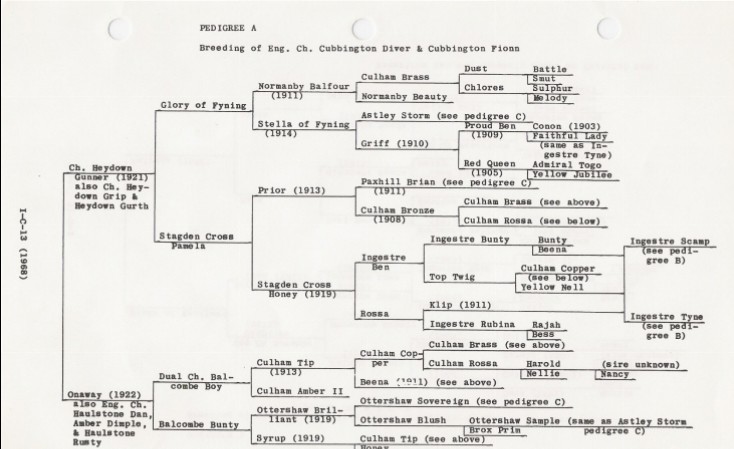

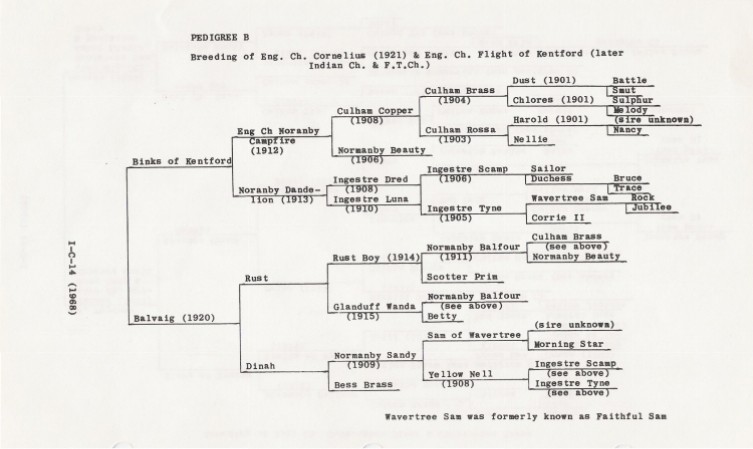

Appended are 3 pedigrees which Mrs. Stonex calls the “A, B, C Pedigrees” and from which matings at least 95% of today’s Goldens can be traced.